History of Public Health Nursing in North Carolina, 1893-2001

Public Health nursing began in the United States and North Carolina with the first graduate nurses who provided nursing services to “the sick poor” in their homes. These nurses provided care to those in need with little concern for financial compensation. They were frequently the only health care professionals available to impoverished people and their families. These early public health nurses were courageous and caring women whose commitment to those they served was challenged daily by the overwhelming problems they confronted and the social obstacles of a society that held little esteem for women who operated outside of the accepted roles of their class and family.

Nineteenth Century

In 1893, Lillian Wald established the Henry Street Nursing Settlement in New York City. Henry Street nurses, trained in hospital based, bed side nursing care, took their knowledge and skills into the homes and neighborhoods of New York’s poor and immigrant communities. In the beginning, public health nurses primarily took care of the sick poor in their homes. Lillian Wald and the Henry Street nurses came to the realization that sickness found in the home was often interrelated with issues in the larger society. The Henry Street Settlement nurses began directing their efforts toward improvements in sanitation, nutrition and education. This emphasis on illness prevention and health promotion took hold across the country and a new dimension of nursing practice emerged – that of public health nursing.

Public health nursing began in North Carolina as benevolent societies, civic organizations and groups of public minded citizens hired nurses to home visit the sick poor in their communities. According to Mary Lewis Wyche, in her book The History of Nursing in North Carolina, Amelia Lawrason was the first public health nurse to practice in NC. Born on January 20, 1874 in Fayetteville, she graduated from nursing school in Washington DC in 1902 (or 1903). She went to Wilmington to care for her grandmother and was hired in the fall of 1904 by the Ministering Circle of the King’ Daughters, an ecumenical women’s Christian benevolent organization, to provide home care to the sick poor of Wilmington. Upon her marriage in 1906 she left WIlmington and died in Van Couver, British Columbia, Canada on August 19, 1946.

Early Twentieth Century

In 1911, the Wayside Workers of the Home Moravian Church hired Registered Nurse Percy Powers to work among the people of Salem (now part of Winston-Salem). Nurse Powers also went into East and West Salem schools to inspect the school children for health problems and provide education and follow up with their parents as appropriate. She was the first school nurse in NC. In that same year, 1911, the Greensboro Chapter of the Tuberculosis Association, using funds acquired from the sale of Christmas Seals, hired a visiting nurse, Clara Peck to visit Greensboro residents with tuberculosis in their homes to help them follow recommended treatments. The Associated Charities of Raleigh also employed a visiting nurse in 1911. Around the same time the Young Men’s Benevolent Society of the Second Presbyterian Church of Charlotte paid the salary of a visiting nurse for their city.

In 1911, the Wayside Workers of the Home Moravian Church hired Registered Nurse Percy Powers to work among the people of Salem (now part of Winston-Salem). Nurse Powers also went into East and West Salem schools to inspect the school children for health problems and provide education and follow up with their parents as appropriate. She was the first school nurse in NC. In that same year, 1911, the Greensboro Chapter of the Tuberculosis Association, using funds acquired from the sale of Christmas Seals, hired a visiting nurse, Clara Peck to visit Greensboro residents with tuberculosis in their homes to help them follow recommended treatments. The Associated Charities of Raleigh also employed a visiting nurse in 1911. Around the same time the Young Men’s Benevolent Society of the Second Presbyterian Church of Charlotte paid the salary of a visiting nurse for their city.

In 1912, the American Red Cross Town and Country Nursing Service was established to provide skilled nursing care and health instruction in remote rural regions across the United States. Between 1915 and 1935, 52 NC chapters of the Red Cross shared expenses with the national Red Cross to employee Town and Country nurses in their communities.

These early public health nurses were joined in the decade of the 19- teens by public health nurses employed by local governmental agencies. In 1910, the City of Asheville hired Jane Brown, RN to provide general follow up bedside nursing for patients discharged from recent stays in area hospitals. In 1912, Durham City/County health department hired Mrs. Clyde Dickson as a visiting nurse and in 1915, Mrs. Emily Pickard was hired by the Durham City School Board to be the first school nurse in Durham.

By 1917, 2 nurses were providing general bedside nursing for the sick poor in Charlotte.One was paid by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company and the other by the Young Men’s Benevolent Society of the Second Presbyterian Church. Just 4 years later, in 1921, there were 17 Public Health Nurses in Charlotte paid by various agencies including the American Red Cross, 2 textile mills and the city health department. Guilford County hired Mary Horry, RN to do Infant Relief Work in 1918 and in 1919 it hired Mrs. Blanche Lamb who became the first school nurse hired by a county health department in NC.

Lydia Holman

A notable exception to the pattern of nurses being hired by benevolent associations and local governments to provide some measure of public health, home health and school nursing was the work of Lydia Holman of Mitchell County. Lydia Holman came to the small town of Ledger in the mountains of North Carolina in 1900 to provide private duty care for a wealthy woman, who was very ill with typhus at her vacation home in Mitchell County (Hawkins, 1998).

Holman observed many local people suffering from blindness, deafness, orthopedic deformities, premature deaths and illnesses that could be prevented and she realized she had to do something about these conditions. Traveling on horseback over tortuous mountain roads, up stream beds and over the high mountains, she delivered hundreds of babies, performed minor surgery and dentistry, immunized folks against typhoid and fought epidemics of tuberculosis, pellagra, smallpox and measles.This “wiry little woman” spent 58 years caring for rural, Appalachian families in and around Mitchell, Yancey and Avery Counties (Rosner, 1924).The range of Holman’s accomplishments is staggering.She was a nurse, midwife, health educator, dentist, social worker and sometimes physician for hundreds of people in a sixty mile area.

Ledger, at that time of Holman’s arrival, was an isolated Appalachian village about thirty miles from the nearest railroad, with no paved roads, no electricity, no running water, no newspaper, no hospital, and no trained nurses.As her patient’s health improved, Holman was increasingly called on by local residents to attend to their illnesses (Wyche, 1938). Wyche writes about Holman this way:

“Miss Holman made a study of the living conditions of the people and found them lacking in many respects. She became attached to the mountain folk and felt that she could be of use to them in combating disease and in teaching hygiene and dietetics … For many years she not only did her housework and cooking, but cared for her horse as well. At any hour of the day or night she answered the calls of the people, riding alone for miles to attend a person in need.Her arduous duties have been attended by danger and discomforts…” (p.59)

In a 1915 report to her supporters, Holman describes some of her activities as teaching classes in hygiene and nutrition, working to control epidemics of chicken pox, scarlet fever, measles and camp itch, holding an immunization campaign against typhoid and distributing donated toothbrushes and toothpaste while teaching the importance of dental health in the community. In addition to her nursing work, Holman established a small lending library, kept a demonstration garden so local people could learn to grow a wider variety of fruits and vegetables to supplement their diets and distributed hundreds of donated toys at Christmas time to local children (Lydia Holman, 1960).

As the years went by progress came to western North Carolina, including Mitchell County. A few physicians moved into the area and were upset by the breadth of Holman’s work and had her arrested for practicing medicine without a license. Holman later wrote about the experience this way:

As the years went by progress came to western North Carolina, including Mitchell County. A few physicians moved into the area and were upset by the breadth of Holman’s work and had her arrested for practicing medicine without a license. Holman later wrote about the experience this way:

“It was nicely done. He [the arresting officer] read his warrant and said “Now, Miss Holman, don’t let it worry you … It will cost you every cent of fifty dollars, and I would not do it. There ain’t no reason why you should pay anything”. I took the man’s advice and spent the whole day waiting for the people in the courthouse to decide what was to become of me. The Solicitor read a very nice little piece of scripture and dismissed the case … After court, twenty mountain men or more took credit for having the case thrown out. Then they came to assure me, all the neighbors and people I had never heard of, that I should go on with the work … they would be quite willing to hire teams and come to my defense.” (An informal report, 1915).

She did continue with her work. By the 1920s, state and federal monies were starting to become available for public health work and Holman was put in charge of administering these funds in Mitchell County.

In addition to intelligence and care, Holman also demonstrated ingenuity. By 1930 there were sufficient paved roads in the county to make traveling by car faster and easier than horseback. Holman had no extra funds with which to purchase a car so she wrote President Herbert Hoover saying if she had a nice car she would be able to drive voters to the polls to vote for him in the upcoming presidential election. Soon, a brand new 1931 model A Ford was delivered to Holman from the White House (A model “A” angel, 1990). In 1936, at age 68, Holman was elected to the Mitchell County Board of Health, becoming the first female elected official in the county. Holman spent her retirement years in her beloved Mitchell County, dying in 1962 in the VA hospital in nearby Asheville.She is buried in a plain grave in the Spruce Pine cemetery close to where she spent her life in unselfish service to her fellow citizens (Lydia Holman dies, 1960).

State and Federal Involvement

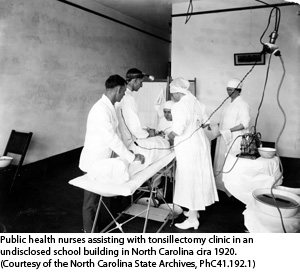

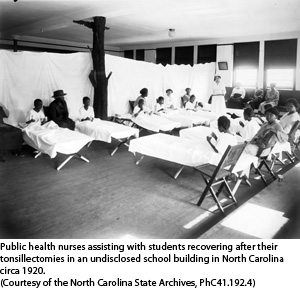

Following the lead of city and county governments, the state government of NC began its involvement in public health nursing in 1919. In that year, two programs funding public health nursing were initiated. The first focused on school health nursing. Six schools nurses were hired by the NC State Department of Public Health to assess school children across the state for growth, dental status, infections, particularly of the tonsils and adenoids and to look for other less common problems. The nurses inspected each child from first through sixth grade at three year intervals. These first six nurses who worked together for over 18 years were Cleone Hobbs of Clinton, Birdie Dunn of Raleigh, Cora Beam of Fallstone, Kate Livingston of Wagram, Flora Ray of Sanford and Mrs. HP Guffy of Statesville. Their first biennial report released in 1921, shows the nurses inspected 92,566 children and conducted clinics for immunizations, tonsil and adenoid removal and dental treatments. They also provided many health lectures to parent groups and to teachers about a wide variety of topics. Many years later, Wyche wrote about these nurses this way: “they have traveled on foot, horseback, on rafts, by boat, tram cars, ox-carts –any way to reach the ‘forgotten” child.”

Following the lead of city and county governments, the state government of NC began its involvement in public health nursing in 1919. In that year, two programs funding public health nursing were initiated. The first focused on school health nursing. Six schools nurses were hired by the NC State Department of Public Health to assess school children across the state for growth, dental status, infections, particularly of the tonsils and adenoids and to look for other less common problems. The nurses inspected each child from first through sixth grade at three year intervals. These first six nurses who worked together for over 18 years were Cleone Hobbs of Clinton, Birdie Dunn of Raleigh, Cora Beam of Fallstone, Kate Livingston of Wagram, Flora Ray of Sanford and Mrs. HP Guffy of Statesville. Their first biennial report released in 1921, shows the nurses inspected 92,566 children and conducted clinics for immunizations, tonsil and adenoid removal and dental treatments. They also provided many health lectures to parent groups and to teachers about a wide variety of topics. Many years later, Wyche wrote about these nurses this way: “they have traveled on foot, horseback, on rafts, by boat, tram cars, ox-carts –any way to reach the ‘forgotten” child.”

Also in 1919, the state partnered with the American Red Cross to establish the Bureau of Public Health Nursing and Infant Hygiene. Nurse Rose Ehrenfeld was appointed its first director. Its mission was to improve maternal/child outcomes in the state. Ehrenfeld was born in 1878 in Kentucky. She remained in her job in Raleigh from 1919-1923.

Both the "Spanish Flu" world wide pandemic in 1918-1919 that killed 0ver 9,500 NOrth Carolinians, along with over 3,000 wounded NC veterans returning from WWI, increased the need for public heealth nurses, infrastructure and funding.

In 1921, a year after women got the right to vote, the federal government became involved in funding public health nursing programs.The US Congress passed the Sheppard Towner Act over the objections of the American Medical Association. This legislation authorized federal aid to states for maternal and child health, and welfare programs.States had to provide matching funds.Using $27,259 of Sheppard Towner Act monies and state funds, on April 1, 1922, NC reorganized the Bureau of Public Health and Infant hygiene into the Bureau of Maternity and Infancy.Under Nurse Ehrenfeld’s leadership a program of midwife education and supervision began. In the 1920’s over 30% of births in NC were attended by the approximately 5,000 lay midwives in active practice at that time.In the early 1920s the state legislature passed the Model County Midwife Regulations, which included requirements that lay midwives have a physical examination and instruction and demonstrations given by doctors and nurses inthe procedures of a normal delivery. A 1928 report in the Health Bulletin shows that state public health nurses delivered midwife classes in 30 counties in the state. In 1921 there wre 25 public health nurses, 18 of which were totoally or partially funded by th American Red Cross. Their average monthly report show 30 Home visits for bedside care, 44 for infantt welfare, 9 for pre-natal care, 12 for Tuberculosis care, 37 for "instructive or social service" concerns, in addition to the home visits (132 per month) these nurses averaged 2 baby care demonstrations, instructing 2 midwife classes, examining 110 school students, 4 classroom lectures, 5 lectures to the general public and instructed 2 classes of Home Hygience and Care of the Sick.

Lula Owl Gloyne

In 1921 the US Congress also passed the Snyder Act which was the principal legislation authorizing federal funds for health services to Native American tribes. In ratifying the Snyder Act, the federal government sought to provide appropriations "for the benefit, care and assistance . . . and for the relief of distress and the conservation of health . . . for Indians tribes throughout the United States."

The first North Carolina Eastern Band Cherokee Registered Nurse, Mrs. Lula Owl Gloyne, was employed as a public health nurse using Snyder funds. Lula Owl was the first of ten children born to Daniel Lloyd Owl a Cherokee blacksmith and Nettie Harris Owl, a Catawba Indian and traditional basket maker and potter.Lloyd did not speak Catawba and Nettie did not speak Cherokee, but both parents shared a basic knowledge of English which became the primary language in the household.Mrs. Mary Wachacha, Lula Owl’s granddaughter, surmises that the Owl children’s mastery of the English language explains why all seven siblings who survived to adulthood went on to professional careers. Lula Owl attended a mission school on the Qualla Boundary and then went to Hampton Institute in Hampton, Virginia to complete her education (M.Wachacha, personal interview, December 11, 2008).

After graduating from Hampton in 1914, she spent a year in the classroom teaching Catawba children in Rock Hill, SC. During that year, Owl decided to follow her calling to become a nurse.Mentors from her Hampton days arranged for Owl to enter the Chestnut Hill Hospital School of Nursing in Philadelphia, PA (M.Wachacha, personal interview, December 11, 2008).

All nursing students at Chestnut Hill Hospital were required to attend church services weekly. Owl was raised a Southern Baptist, but she had no way of getting to the Baptist church located many miles away.The only church within walking distance to the hospital was St. Paul’s Episcopal Church.Owl started attending this church.Members of the church “adopted” her.They took up love offerings (cash contributions), gave her used clothing, and upon graduation, arranged a job for her as the missionary school nurse at the St. Elizabeth’s Episcopal School on the (Sioux) Standing Rock Reservation in Wakapala, S.D (M. Wachacha, personal interview, December 11, 2008). When Owl graduated in 1916, she was awarded the Gold Medal in Obstetrical nursing and became the first EBCI Registered Nurse (Carney, 2005).

In 1917, the United States joined the allies in fighting World War One (WWI). The Red Cross and the Army Nurse Corps encouraged all Registered Nurses to serve their country during wartime. Owl had planned on going to Europe to be a field nurse for the U.S. Army, but failed the “sea worthy” exam due to extreme seasickness. Instead, she was assigned to Camp Lewis in Washington State as a Second Lieutenant in the Army Nurse Corps (M.Wachacha, personal interview, December 11, 2008).Owl was the only Eastern Band Cherokee Indian to serve as an officer in WWI (Finger, 1992).

While in South Dakota, Owl met Jack Gloyne, an Army enlistee passing through the west on his was to Camp Lewis. They rekindled their acquaintance at Camp Lewis, but since she was an officer and he an enlisted man, fraternization was prohibited. Despite the ban, they were secretly wed in 1918. After the war ended they spent a short time in Oklahoma while Owl (now Gloyne) cared for a sick family member. Around 1921 the couple returned to Cherokee, NC to set up housekeeping (M. Wachacha, personal interview, December 11, 2008).

At that time, Cherokee did not have a hospital or a full time doctor.Gloyne was the first professional health care provider available to help the people on the Qualla Boundary (Finger, 1992). She recalls her early years as a nurse in Cherokee this way (Carden, 1983):

“There was no hospital in Cherokee then, just a clinic at the Quaker grade school and a doctor who worked there part time. When I came home they asked me to help out and at first I worked without pay. I did all the outside work.I got called to homes all around here. I didn’t have a horse or a wagon back then, though some people had ox driven carts and a few had wagons, so I had to make my calls on foot.I got caught in places (too far from the doctor) where I’d just have to do what had to be done.Men got cut up and I’d have to sew them up.Women would call on me to deliver their babies. Today it would be illegal to do a lot of that, but back then there was no one else.”

Nurse Gloyne remained active in her community providing nursing care and volunteering for numerous community organizations until her death in 1989.

The Great Depression and the New Deal

The stock market crash of 1929 leading to the Great Depression of the 1930s changed the nature of public health nursing. The Federal government through programs such as the Federal Emergency Relief Act, the Civil Works Administration, the Works Progress Administration and most importantly the Social Security Act funded programs that expanded the scope and depth of public health nursing activities throughout the country. These New Deal programs had significant impacts on the health of many North Carolinians.Tens of thousands were immunized against diseases, attended clinics and received treatments for hookworm, syphilis and other contagious diseases, were home visited by nurses for prenatal and home health care and were educated on many important health issues of the day. The Social Security Act, and more recently Medicare and Medicaid, fund specific programs instead of giving money to state and local health departments to dispense as they see fit. For the last 75 years, much of our work in public health has been driven by which programs have been funded by the Social Security Act and later by Medicare and Medicaid. For instance, the Social Security Act made money available for maternal child health programs and for crippled children in 1935. Public health nurses could be hired using federal money for these two program areas. In 1938, the SSA began funding sexually transmitted disease prevention and education programs and in 1944 added Tuberculosis control to the list of federally funded health services.Local health departments responded by starting and/or enhancing programs in the areas in which they could receive SSA monies. Even today, many public health nurses are hired in areas for which federal funds are available, rather than where the need may be greatest.

The number of public health nurses employed by government agencies in North Carolina rose from 65 in 1933 to 297 in 1940. The number of county governments participating in public health work increased from 47 in 1934 to 81 by 1940. In 1934, 1,822,961 North Carolinians had access to at least some public health nursing. That number tripled by 1940 to 3,132, 192.Due to these New Deal public health nursing programs, North Carolinians were experiencing better health, nutrition and a generally better quality of life.

In 1930, Amy Louise Fisher was hired by the Watauga Lutheran Mission in Boone NC to work as a parish nurse. When New Deal funding became available in 1935, Fisher became the first public health nurse in Watauga County.In a 1936 article for the journal Public Health Nurse, Fisher described her new situation this way:

“Last year was the first year the health department has been in existence here and we tried to cover practically the whole county. Over 5,000 people took the typhoid fever vaccine and 1,625 babies and children were given diphtheria toxoid.There are about 50 schools in the county, and we plan our schedule that we may get to the most inaccessible ones before bad weather sets in. … We don’t try to go to Lower Elk after a hard rain because you ford the creek 22 times and some of the fords are pretty deep.”

Fisher also taught a class for midwives. Over three sessions, lay midwives learned the proper care of mothers and newborns including how to sanitize instruments and the importance of hand washing.Fisher reported one of her students’ reactions to the class this way: ”Law honey, I’ve catched hundreds of babies and I ain’t never gone through all this fixing before.”

Almost every county in the state took advantage of New Deal programs and money to establish or upgrade their public health programs. As these new public health nurses quietly went about their work, citizens began to understand that everyone had a stake in better sanitation, nutrition and the prevention and treatment of disease.As people experienced better personal and community health, they voted for Roosevelt and the New Deal programs again and again and again.

Captain Mary Mills, International Public Health Nurse

During the first half of the 1940’s most of the country’s attention, manpower and funds were directed to fighting and winning World War II. Hundreds of North Carolina nurses joined the war effort abroad and at military basses and VA hospitals at home.The end of World War II brought a new urgency for international peace and understanding.The United Nations was founded to provide a forum for world leaders to discuss their differences and to avert future wars. This spirit of internationalism was also reflected in US foreign policy as the United States expanded its missions to other countries through foreign aid and programs such as the US Public Health Services’s Office of International Health. One Tarheel nurse, Captain Mary Mills, distinguished herself by offering her knowledge and experience as a public health nurse and midwife to people around the globe.

Born in 1912 and raised near Waltha in Pender County, one of eleven children and the granddaughter of slaves, Mary Mills brought health and hope to people around the world. For nearly three decades Captain Mills labored in poor countries including Liberia, Lebanon, Chad, Viet Nam and Cambodia, organizing maternity wards, child health clinics and nursing schools (Steelman, 1998).

She received her early learning in a one teacher schoolhouse in the days when segregation ruled and educational opportunities for rural, African American children in North Carolina were deplorable. Mills was an exceptional student and completed as much schooling as was available to her in Pender County. During the height of the Great Depression, Mills made her way to Durham, NC where, in 1934, she graduated from the Lincoln Hospital School of Nursing and became a registered nurse. Mills worked as a public health nurse and then in advanced practice as a Nurse-Midwife while she completed her education. She earned a certificate in public health nursing from the Medical College of Virginia, a certificate in midwifery from the Lobenstein School of Midwifery in New York City, a Bachelors and Masters degree from New York University as well as a graduate certificate in health care administration from George Washington University in Washington DC.In 1946, Mills returned to North Carolina to direct the public health nursing certificate program at North Carolina College (now NC Central University) in Durham. That same year, she was commissioned as an officer in the US Public Health Service (Carnegie, 1995).

Mills began her distinguished career in transcultural and global nursing in February, 1946 when she joined the Office of International Health with the United States Public Health Service Mission in Monrovia, Liberia. While in Liberia, she created some of the country’s first health education campaigns, she initiated a national public health library and she advocated legislation to strengthen nursing as a profession (Mary Mills return, 1951).Her work in Liberia was described in a piece in the American Journal of Nursing in 1956 this way (Untitled article, 1956):

“From 1946 until 1952 she served as chief nursing officer for the USPHS in Liberia, West Africa.In addition to trips into the interior with her colleagues to set up immunization stations and health centers, she helped organize and establish the Franklin D. Roosevelt Memorial Children’s Ward at the government hospital in Monrovia and she was instrumental in organizing the Tubman [named in honor of Harriett Tubman] National School of Nursing.Liberia invested her Knight Official of the Liberian Humane Order of African Redemption.”

After a short period back in the United States for study, rest and family visits, Mills, who had been promoted from the rank of major to that of Lt. Colonel, then Colonel and finally Captain, received a USPHS assignment to Beirut Lebanon in January, 1952.On her way from North Carolina to Beirut, she represented the United States at conferences of the International Council of Nurses and the World Health Organization.In Lebanon, Mills worked hard to establish the country’s first school of nursing and after its successful beginnings was awarded the Order of the Cedars, one of that country’s highest awards for service.A nursing dormitory at the school was named in her honor (Carolina nurse, 1957).

In her twenty year career with the Office of International Health, Mills was an ambassador of good will representing North Carolina and the United States around the globe. She provided health education, nursing care and midwifery services to countless suffering individuals and families in Liberia, Lebanon, South Vietnam, Cambodia and Chad.In those countries, Mills worked on small pox and malaria eradication campaigns, sanitation, hygiene and nutrition health education programs, and the establishment of maternal-child health clinics (Centennial committee, 2003). She is fluent in five languages: Arabic, French, Cambodian, African dialects and English. Additionally, in each country where she worked she was instrumental in initiating or expanding schools of nursing.Leaders of every country in which she worked bestowed honors and awards on her for her untiring efforts to improve the quality of life and health for all citizens of the world (Carnegie, 1998).

In 1966, Captain Mills returned permanently to the United States taking a job with the US Department of Health, Education and Welfare as a nursing consultant in the Migrant Health Program. She provided program, policy and political advice about migrant health care and other public health issues to the Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare who in turn sits in the Cabinet advising the President. In this capacity, she went to Finland, Germany and Denmark to study their national health care systems and bring back ideas that might be put to use in the United States. She represented the United States at nursing, midwifery and public health international conferences in Mexico, Canada, Germany, Australia, Italy and Sweden.Mills has been an active member and officer of many professional associations including the American College of Nurse Midwives, National League for Nursing, the Frontier Nursing Service, the American Public Health Association, American Nurse Association, North Carolina Nurse Association (District 11), and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

During her 10 years at the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, Mills received numerous awards in the United States honoring her contributions to all people at home and around the world. These include a US Public Health Service Distinguished Service Award, Princeton University’s Rockefeller Public Service Award, the American Nurse’s Association Mary Mahoney Award, North Carolina’s highest honor, the Long Leaf Pine Award, an honorary Doctor of Science degree from Tuskegee University and an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Seton Hall University.Mills retired from government service in 1976 to her beloved Pender County.She remains an active volunteer in several local organizations that help others and advance nursing.Her story is virtually unknown, yet her contributions to our profession are almost beyond words.

While Mills was making a difference around the world, a major event for North Carolina public health nurses in the late 1940s was the opening of the Public Health Nursing certificate program at the School of Public Health at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. By law and custom, this program was only available to white nurses. Ruth Hay, a national leader in public health nursing education was appointed to establish the UNC Department of Public Health Nursing at the School of Public Health. Hay was the first female professor appointed to the University's faculty. Up to that time, the only nursing education available in North Carolina was through hospital diploma programs.While those programs trained excellent in-patient, bedside care nurses, there was no classroom or clinical education available in public health nursing in our state.With this new program, nurses could spend a year in Chapel Hill and receive education, experience and a certificate in public health nursing. In 1946, the department instituted a cooperative program with NC Central in Durham, whose African-American students were denied admission to UNC. Under the leadership of Lincoln School of Nursing graduate Mary Mills, African American registered nurses were able to earn a public health certificate after one year of study at NC Central.When Ruth Hay left the School of Public Health, Margaret Dolan, probably the most important figure in public health nursing to come from North Carolina, took her place.

Margaret Dolan

Margaret Baggett Dolan was the 5th of nine children born to John and Allene Keeter Baggett on March 17, 1914 in Lillington, NC. She decided to become a nurse and enrolled in the Georgetown University School of Nursing in Washington, DC. She graduated with her Nursing Diploma in 1935, at the height of the Great Depression. In 1944 she went back to school and earned her BS degree in Public Health Nursing from UNC-Chapel Hill School of Public Health and in 1953 she graduated with a Masters Degree from Teachers College, Columbia University. After stints as the nursing supervisor at the Greensboro City Health Department, the Baltimore County Health Department and the US Public Health Service, Dolan came back to Chapel Hill in 1950, as a faculty member in the School of Public Health’s Public Health Nursing program. She stayed at the UNC School of Public Health until her death 23 years later in 1973, working her way up from Associate Professor to Chair of the Public Health Nursing Department.

While Dolan lived and taught in her beloved Chapel Hill, she was a major figure on the national nursing stage. She has been the only nurse to serve as President of the American Nurse Association, the National Health Council, the American Journal of Nursing Company and the American Public Health Association. Working with Dean Lucy Conant of the UNC School of Nursing and Dr. Isaac Taylor of the UNC School of Medicine, Dolan was instrumental in developing one of the first nurse practitioner programs in the country at UNC-CH. Throughout the 1950s, 1960s and early 1970s, Dolan frequently testified before the US Congress on issues related to public health, nursing and health care in general.

Dolan also served as a consultant to the US Department of Defense, the US Surgeon General, and the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. She was national treasurer for Sigma Theta Tau, vice president of the American Nurses Foundation, held various offices in the NC and US Tuberculosis Societies, the NC and National League of Nursing and in the American Association of University Professors.Dolan represented the United States at International Council of Nursing meetings in Frankfort, Germany and Melbourne, Australia.She consulted about health matters with the governments of Ghana and Thailand.

Dolan was a sought after speaker, a prolific author and a gifted teacher. She was an advocate for racial minorities, the uninsured and vulnerable people everywhere. Believing health care ought to be a right, she worked tirelessly through education, legislative advocacy and public persuasion to bring changes to law and policy to make high quality health care available to all who needed it. To this end, she was an early proponent of advanced practice for nurses, universal health insurance, and government funding for expanding healthcare facilities and training health care personnel.

Government Programs

The most important changes to public health nursing across the nation, including in NC in the 1960s was the enactment by the US Congress of the Medicaid and Medicare programs.

Medicaid and Medicare funds provide health services to low-income children, their caretaker relatives, the elderly, the blind, and individuals with disabilities. Medicaid is the largest source of funding for medical and health-related services for America's poorest people. Medicare is the largest source of funding for medical and health related services for those over 65 years of age. Federal monies were made available to local public health departments to expand both clinic based and in home care for these groups of people. Many new public health and home health nurses were hired and many new programs, including EPSDT screening, family planning clinics, pre-natal clinics and what was then called crippled children’s services were begun and/or expanded.In patient psychiatric hospitals and community mental health clinics also benefited and grew through using Medicaid and Medicare funds.By the 1960s NC had several baccalaureate programs in nursing including those at UNC-CH, NC A&T, WSSU and Duke University, whose graduates were prepared to practice public health nursing.

The increasing number of and effectiveness of pharmaceuticals contributed to changes in public health nursing in the 1960s.The introduction of INH to treat tuberculosis meant that people with TB no longer had to be isolated in sanitoria, but frequently needed home care and monitoring. In 1966, 30 full time “Tuberculosis Nurses” work in 17 NC health departments.In the smaller health departments there was usually a nurse assigned to tuberculosis work along with other responsibilities. In the 1960s measles, mumps, rubella nd oral polio vaccines were approved by the FDA creating a greater need for immunization clinics. The birth control pill became available in the 1960s increasing the need and desire for family planning clinics and nurses to staff them.

The increasing number of and effectiveness of pharmaceuticals contributed to changes in public health nursing in the 1960s.The introduction of INH to treat tuberculosis meant that people with TB no longer had to be isolated in sanitoria, but frequently needed home care and monitoring. In 1966, 30 full time “Tuberculosis Nurses” work in 17 NC health departments.In the smaller health departments there was usually a nurse assigned to tuberculosis work along with other responsibilities. In the 1960s measles, mumps, rubella nd oral polio vaccines were approved by the FDA creating a greater need for immunization clinics. The birth control pill became available in the 1960s increasing the need and desire for family planning clinics and nurses to staff them.

With an increasing number of citizens having access to health care due to Medicaid and Medicare funding and an increasing variety of programs available such as family planning and immunization clinics, a need for for health care providers emerged. In the 1970s, North Carolina was one of the first states to meet this need through the training and employment of nurse practitioners. In 1971, the NC Legislature appropriated $75,000 to start NP training programs at5 baccalaureate school of nursing. The early programs were certificate programs and nurses did not have to have a BSN to enter.Most of the first 188 NPs in NC were practicing Public Health Nurses who returned to their health departments to work as NPs after their training. In 1977 the US Congress passed the Rural Health Clinic Services Act which provided reimbursement to NPs who practiced in designated rural health clinics.NC rural health clinics including those in Walstonburg, Tarboro and Hot Springs employed NPs using these funds.

In the 1980s the US Congress added case management services to the list of services billable to Medicaid and Medicare. Many NC health departments hired public health nurses to institute the case management Baby Love program for low income mothers and their babies. Baby Love offered low income pregnant women and their babies early, continuous, comprehensive health care. Hospice services also became reimbursable during the 1980s so many local health departments added hospice nurses and services to their home health programs in the 1980s.

Another national effort that affected public health nurses in NC in the 1980s was the beginning of the Healthy People initiative. Experts in public health and public policy, including many nurses, created a list of 15 goals with over 300 measurable outcomes that, if implemented within the decade of the 1980s would greatly improve public health and wellbeing. These goals included reducing high blood pressure; expanding family planning services; increasing the number of fully immunized children, decreasing the incidents of sexually transmitted diseases; increasing fluoridation and dental health;increasing surveillance and control of infectious diseases, including HIV/AIDS;increasing tobacco prevention efforts through education and policy changes; reducing substance abuse; increasing physical fitness and exercise and reducing accident prevention and injury. The Healthy People initiative continues to serve as a blueprint for much of our work in public health.

The attacks of September 11, 2001, put an emphasis on planning and preparing for future acts of terrorism. Public health nurses in NC have taken leading roles in this effort.

NC public health nurses today continue the work of the first public health nurses in our state by improving maternal/child health, reducing infectious diseases through immunization and education, encouraging people to adopt healthy lifestyles through physical activity and better nutrition, caring for children in the schools and helping people die with dignity. If some form of national health insurances passes the US Congress, there will be increased demands for our services and expertise. We can gather inspiration from those that have gone before us so 100 years from now, the public health nurses of NC can point to us proudly for the efforts we are making to improve the health and well being of all North Carolinians.

References

- Ehrenfeld, R.M. (1919). The evolution of public health nursing. American Journal of Nurisng, 20(1). pp 14-18

- Ehrenfeld, R.M. (1920). Does your county have a public health nurse? The Health Bulletin. p7-8

- The Health Bulletin, the official publication of the NC Board of Health 1886-1973.

- 1918 report from the state of NC about county services including public health nursing. pp. 128-130.

- Statistics from 1919 article in the Journal of Public Health Nursing about public health nurses in NC.

- List of Public Health nurses in NC in 1922 with locations and sources of funding (PDF).

- The 1944-45 Health Bulletin has a comprehensive history of public health in NC including 75 references to nurses.

- NC Board Of Health Timeline published in the 29th Biennial Report, 1941-1942 Mentions of Nursing.

- Herring, H. (1929). Welfare Work in Mill Villages. [excerpts]

Public Health Nursing and the COVID-19 Pandemic, 2019-2021

Select articles from the first two years of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Additional reasearch and contibutions to this ongoing topic are encouraged.

- Cygan, H., Bejster, M., Tibbia, C., & Vondracek, H. (2021, Oct. 6). Impact of COVID-19 on public health nursing student learning outcomes. Public Health Nurse. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fphn.12978

- Melvin, S.C., Wiggins, C., Burse, N., Thompson, E., & Monger, M. (2020, July). The Role of Public Health in COVID-19 Emergency Response Efforts From a Rural Health Perspective. Preventing Chronic Disease: Public Health Research, Practice, and Policy, 17(E70). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2020/20_0256.htm. (PDF copy).

- Pittman, P., & Park, J. (2021). Rebuilding Community-Based and Public Health Nursing in the Wake of COVID-19. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 26(7). DOI: https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol26No02Man07

- Vessey, J.A. & Betz, C.L. (2020). Everything Old is New again: COVID-19 and Public Health. J Pediatr Nurs, 52, p. A7-A8. PMCID: PMC7138181

- Walden University. (2020). The Role of the Public Health Nurse in a Pandemic. Public Health Nursing Online. Walden University. Available online: https://www.waldenu.edu/online-masters-programs/master-of-science-in-nursing/msn-public-health-nursing/resource/the-role-of-the-public-health-nurse-in-a-pandemic. (PDF copy).