"The functions of the NCSNA are to foster high standards of nursing practice, to promote the professional and educational advancement of nurses, and to promote the welfare of nurses – all to the end that all people will have better nursing care." Marie Noell, 1965

Lillie Marie Brock was the eldest of six children born to Minnie and Thomas Brock of Durham on October 25, 1900. Her father was a foreman in a local tobacco factory while her motherwas a homemaker. In 1922, she was one of three graduates from the local and highly regarded Watts Hospital School of Nursing. She soon passed the State Board of Nursing exams and in October of the same year, married Charles Noell. She spent most of the 1920s practicing private duty nursing and raising the couple’s two sons.

As the children grew, she became more involved with the North Carolina Nurse Association, serving in various district and state offices. In 1939 Noell was elected President of the organization. Shortly into her second term as President of NCNA, Noell transitioned to becomethe new Executive Secretary of the NCNA, a post she held for the next 26 years.

Reporting in the Newsletter of the North Carolina State Nurses’ Association described Noell as:

… active in nursing organizations, both district and state, since her graduation in 1922. She has visited every district in the state and is most thoroughly familiar with the affairs of the local nursing organizations. She has been instrumental in getting eight-hour duty established. She is interested in all civic affairs and has taken an active part in the clubs in Durham.

Noell quickly embraced her new responsibilities. As the only paid employee of NCNA she; recruited new members; provided member services. lobbied the state legislature on behalf of nursing interests; launched and edited the Tar Heel Nurse; raised funds; coordinated the annual convention; represented nurses on numerous interagency boards and spoke to the press and interested civic organizations on behalf of the NCNA. By all reports, Noell excelled in all these areas.

She took the helm of the NCNA in fraught times. The country was still enduring the effects of the Great Depression and was soon to enter World War II. In her second Presidential Message published in the September 1940 Newsletter (the predecessor to the Tar Heel Nurse) she wrote:

With our neighboring nations at war, with profound distress to the East and West of us, and with the serious crisis through which our own country is going, I urge you to heed the duties and responsibilities that as a professional group are ours. We must apply our knowledge and skill to help maintain the security of our fellow man.

As a special agent of the US Public Health Service, Noell collected North Carolina data for a national survey identifying nursing resources available for military duty and/or for staffing stateside hospitals. Survey results revealed a serious national nursing shortage. The country was barely able to meet the nursing needs of the military while maintaining adequate staffing for existing health care facilities. During World War II, Noell led the NCNA efforts to fill every seat in every nursing school in the state; encourage inactive nurses to return to work; and urge every nurse to take on extra responsibilities including becoming Red Cross First Aid and Home Nursing instructors so people could better car for themselves while so many health care providers were in military service.

World War II brought about many changes in health care. On the national level, the vast numbers of returning veterans suffering physical and mental impairments, along with the virtual absence of investments in hospitals and health departments during the Great Depression in the decade before WWII, were catalysts for the US Congress to pass the Hill Burton Hospital Construction Act in 1946. As more hospitals were erected and/or expanded with Hill Burton monies the need for nursing staff grew concordantly.

North Carolina led the nation in draft rejections due to health reasons, almost half the men of draft age suffered from one or more ailments. At the same time, North Carolina was the 11th largest state in populations but was 45th in doctor to patient rations and 42nd in the number of hospital beds per population. These alarming statistics motivated state leaders to implement the “Good Health Plan”. State funding for county hospitals and health departments increased, furthering the need for more nurses.

This increasing need for nurses dovetailed with the rise in maternity known as the “Baby Boom”. During the war years, 1941-1945, millions of men and thousands of women were serving the country away from home and the birth rate was very low. In the decade after WWII, families were reunited, marriage rates soared, and the highest birth rates recorded to date ensued. Many nurses became new mothers and had little interest in a 44-to-48-hour work week.

Nursing is often considered a “calling” where the desire to be of service outweighs financial considerations. Most North Carolina hospital administrators needed more nurses in the late 1940s and 1950s but did not offer attractive working conditions. In 1945, the National Nursing Council published a study titled “A comprehensive program for nationwide action in the field of nursing” that found employers offered insufficient economic incentives to either attract a large number of new recruits or to retain experienced nurses. Major areas of dissatisfaction among nurses were low rates of pay, lack of retirement pensions, and limited opportunities for promotion.

These findings were true in North Carolina as well as the nation as a whole. Noell, as the face and voice of nursing in North Carolina, advocated tirelessly in the decades after World War II for better pay and working conditions for nurses. In the late 1940s Noell and other NCNA leaders established the North Carolina Association of Nursing Students to support nursing students and as a recruiting tool to encourage young women to enter the profession. In her 1952 testimony before the President’s Commission on the Health Needs of the Nation she said in part:

The average hospital in North Carolina paid $175 a month last year to those nurses living at home. If a nurse has small children, she would have to pay $100 a month for someone for staying with those children while she works. She would have to pay income taxes on her own salary and social security taxes on her employee, although that nurse probably would not be covered by social security in North Carolina. All of this would leave less that $50 per month clear income for a 44 - to 48-hour workweek. Most women do not feel the time spent away from their families is worth so little except in times of severe financial difficulty or dire disaster.

Noell’s advocacy for better pay, a 40-hour work week, and inclusion in the Social Security program for nurses working at non-profit hospitals made her subject to hostility from many hospital administrators and physicians. Altha Howell, RN spoke about Noell’s commitment to bettering the working conditions of nurses across the state:

Some of the economic security situations throughout the years have demanded a leadership and a spokesman of rare courage to represent the nurses. Marie Noell had that courage, and she has led and spoken for nurses to spare elected leaders of the Association the threat pf losing their jobs. She has faced hostile employers, she has dealt with impatient nurses, she has wooed an uninformed public, she has suffered humiliations in fighting for better working conditions for nurses. This required personal sacrifices on her part. In the early years, she would leave her family for several days to work with nurses and represent them in seeking improved economic and working conditions. She has traveled day and night to reach or return from distant areas of the state where nurses requested assistance in improving their economic plight.

In addition to her priority of improving pay and working conditions for nurses, Noell was a leader and advocate for racial integration of the NCNA and health care agencies. These issues were related because in 1948 President Truman issued an Executive Order integrating the federal workforce and only allowing collective bargaining and contract negotiations by the US Government with integrated unions. Several nurses working in Veterans Administration hospitals and on military bases in North Carolina formed unions and sought to have contracts covering pay and working conditions. In an address to the delegates of the 1948 NCNA Convention Noell reviewed the lengthy discussions white nursing leaders had about integrating the Association.

And then it was last year that we had another committee and this committee recommended that they [African American nurses] come into the association as soon as possible. At that time our charter or certificate of incorporation included one sentence saying that “only white nurses can belong to this association”. Then came the adoption of the Economic Security Program and it was vitally necessary to amend the charter or certificate of incorporation in order to make a change so that the association could do collective bargaining and it was unanimously agreed by the Board that this sentence be deleted from the charter.

The next year, 1949, the NCNA and the North Carolina Association of Negro Registered Nurses merged. Noell lauded this event:

Since all citizens of North Carolina need adequate nursing care and since the professional nursing organizations are to a great degree responsible for such care, I believe the action taken this morning by the N.C. Association of Negro Registered Nurses, Inc. to dissolve its organization of 27 years standing and to associate itself wholly with the NC State Nurses’ Association will be a great asset in promoting nursing service for all North Carolinians.

Noell advocated integrating schools of nursing, hospitals, and other health care agencies using a financial argument. In 1952 she noted “Social custom which dictates segregation of white and Negro populations has meant a duplication of educational and health facilities which is certainly uneconomical.”

While working on improving pay and working conditions for nurses and pushing for racial integration, Noell also worked with the legislators at the state and national levels to enhance the nursing profession and health care for all people. She encouraged nurses to contact their representatives, to influence many issues of the day. Margaret Dolan, past president of both the NCNA and the ANA remembered Noel’s lobbying skills this way:

Marie Noell has provided us a model for our legislative efforts in the years ahead. This model incorporates the concepts of alertness, education, communication, vigilance, perseverance, and idealism blended with appropriate amounts of realism and pragmatism, enthusiasm and ceaseless effort. These concepts and qualities epitomize Marie Noell’s work in legislation and have crowned her achievements as a legislative representative for the nursing profession – par excellent.

All of her legislative and leadership skills were needed in 1953. For several years the NC Board of Nurse Examiners (Board) and the physician-owned Hamlett Hospital School of Nursing had been in conflict over standards at the hospital’s school of nursing. After years of refusing to upgrade facilities, ensure adequately prepared faculty, and follow the state mandated curricula, in 1952 the Board refused to accredit the nursing school, meaning the graduates could not sit for the State Board Examination and become Registered Nurses. The physician owners of the hospital sued the Board but lost their case. In retaliation, the physicians and their allies got nine legislators to introduce Senate Bill 258 in the spring, 1953 legislative session. This bill would have revised the make- up of the Board to include 4 nurses and 3 physicians who would be appointed by and could be removed at the pleasure of the governor. Nurses appointed to the Board would have had to have been at the bedside in the two years prior to their appointment thus barring nurse educators and administrators from consideration. Further the bill would eliminate most record keeping requirements for schools of nursing.

This bill alarmed nurses across the state and Noell led the campaign to successfully defeat it. In its place a new Nurse Practice Act was passed, legally codifying many guidelines proposed by the NCNA. While some mild compromises had to be reached in the end, the Nurse Practice Act of 1953 strengthened professional nursing in North Carolina. A decade later, Noell led the NCNA to another major legislative victory when the General Assembly passed a bill making registration mandatory for practicing nursing in North Carolina in 1965.

In that same year, the US Congress passed the Medicare and Medicaid Acts, increasing access to health care for millions of poor and elderly Americans. Additional funds were made available for community mental health centers. The need for nurses again exploded in North Carolina as these programs were enacted. The NCNA under Noell’s leadership sought to increase financial aid for nursing students, expand graduate programs in nursing education to have an adequate supply of faculty members and enhance pay and working conditions to make nursing a desirable career.

Noell continued her decades long advocacy for better pay and working conditions for nurses until her retirement in 1967. Knowing her retirement was imminent, Noell received many accolades from the nurses and others in North Carolina. In 1965 her birthday fell during the NCNA Convention. NCNA President Edith Brocker presented Noell with a charm bracelet with medallions representing each district of NCNA. The Wake County district nurse association awarded her the “Nurse of the Year” certificate in 1966. In 1970 she was honored by the North Carolina Health Council for her “long tenure of outstanding leadership”.

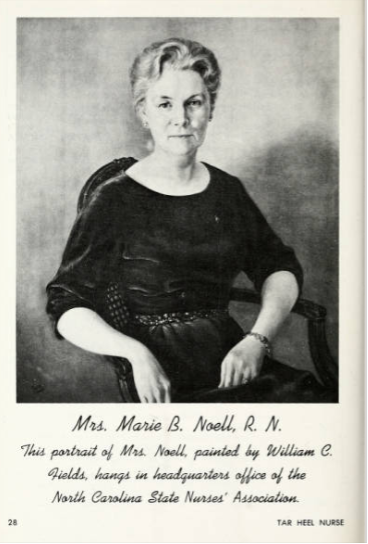

Upon her retirement hundreds of North Carolina nurses gathered at the NCNA headquarters building on Clark Street for “Marie Noell Recognition Day” on June 25, 1967. Her portrait was unveiled and hung in the headquarters building. The September 1967 Tar Heel Nurse dedicated 16 pages to reporting on the Day and reprinting speeches given in Noell’s honor.

A salute to Marie Noell by NCNA President Eloise Lewis was printed in the March 1967 Tar Heel Nurse:

The NCNA moved into a new headquarters in 1975 and named the new building after Noell in recognition of her years of leadership and dedication to upgrading the profession. Noell’s vision and hard work shaped NCNA priorities and accomplishments for a generation. She was well loved and respected. Noell died on June 5, 1988, and is buried beside her husband in the Maplewood Cemetery in Durham.