The Outer Banks are a 175- mile chain of remote and windswept barrier islands that skirt the coast of North Carolina; Ocracoke Island, is one of the most isolated. Before the 1950s, there were no paved roads, electricity, or water and sewer systems on the island. Most Outer Bankers lived a subsistence lifestyle that combined fishing, salvaging shipwrecks, piloting vessels through the inlets, farming and hunting. Ocracoke Village was home to a Coast Guard Station, clam processing plant and working port. Until the 1980s, except for the small hospital the Navy maintained during WWII there were no health care facilities or physicians on the island. It was up to nurse Kathleen Bragg to provide care to Ocracoke residents.

Kathleen Bragg, born on Ocracoke on July 5, 1897, was the daughter and granddaughter of Ocracoke Inlet pilots. When she decided to become a nurse, she attended Park View Hospital School of Nursing in Rocky Mount and graduated first in the class in 1923. A few years after she graduated her father had a heart attack, and she returned to Ocracoke to take care of him and help the family. She was the only trained health care professional on the island. Because she had no mortgage or utility bills, no car, and few grocery bills because most food was grown in the garden, raised on the farms or caught from the sea, she supported herself as an independent nurse, without physician supervision for decades.

Bragg’s neighbors called on her to nurse them when they were ill. Some of her notable cases included a ruptured appendix, blood poisoning and typhoid fever. She also served as the Ocracoke midwife, delivering over 100 babies. When injuries or illnesses were beyond her capacity to help, Bragg assisted in getting her neighbors to the nearest hospital on the mainland.

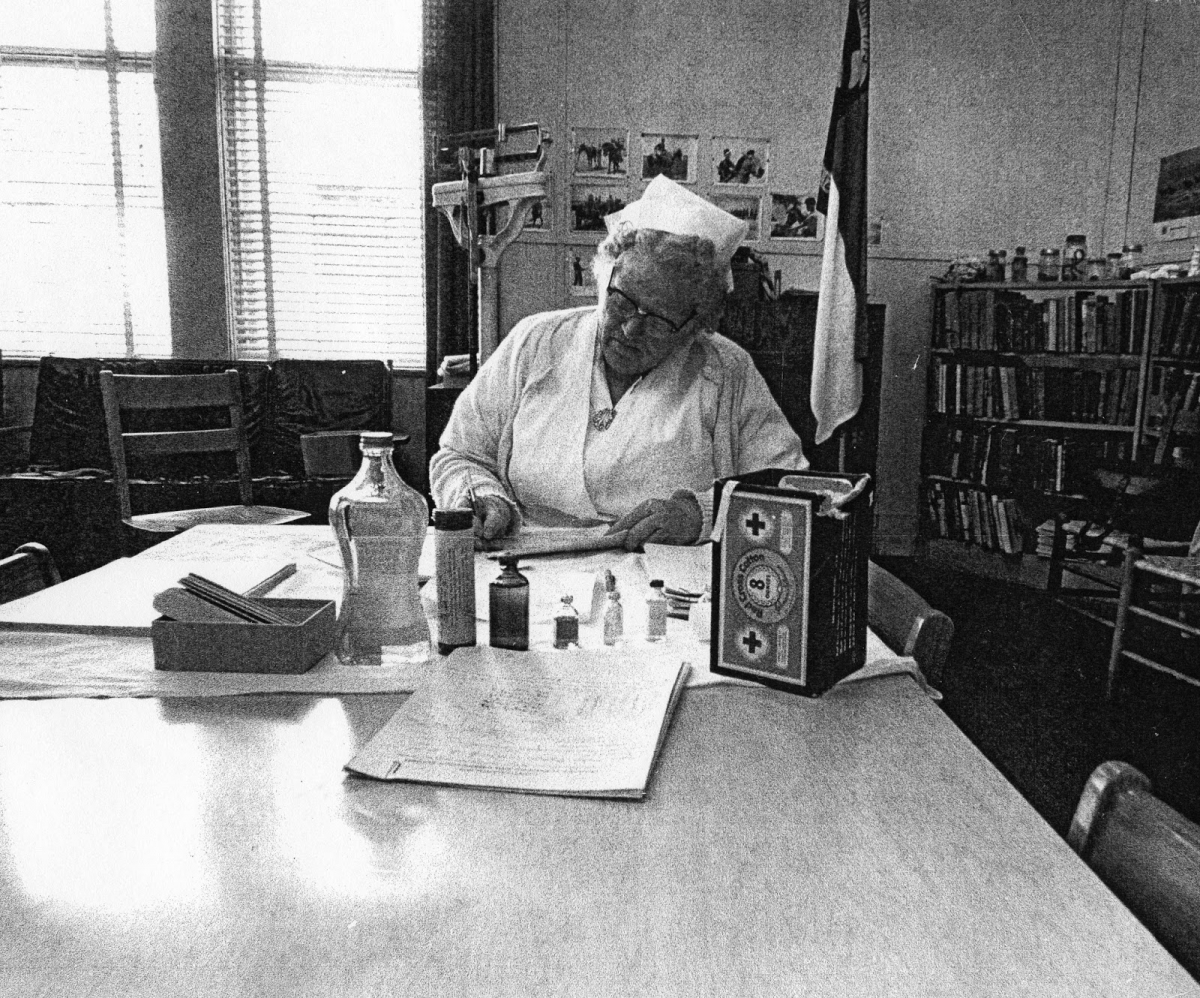

When Hyde County created a health department in the late 1940s, Bragg was hired to function as the public health, home health, and hospice nurse on Ocracoke. She also coordinated eye clinics, pre - schools check-ups, tuberculosis screenings and other health department services on the island. In 1953 Bragg began working as the Ocracoke School nurse. She spent Wednesdays at the school, often administering vaccine injections. As Alton Balance, a local historian, writes in his book, Ocracokers, "high absenteeism was not uncommon on Wednesdays."

When Ocracoke became a tourist destination after WWII, the town map designated her home with the word Nurse to show visitors where they should go if they became injured or ill. A 1958 newspaper article about a flu epidemic on the island read in part:

The only registered nurse on doctorless Ocracoke Island said today she believes a flu epidemic which has struck 300 of the 500 residents now is under control. Mrs. Kathleen Bragg, herself abed with flu, said drugs sent from the mainland and from neighboring Hatteras Island, plus the visit of a Hatteras doctor, had controlled the situation. Dr. Garland Wampler, U.S. Public Health Service officer at Hatteras treated as many as he could among the estimated 200 bed patients on Ocracoke. Mrs. Bragg said he didn’t plan to return unless she told him the situation was beyond her control.

Nurse Bragg lived quietly, rendering valuable nursing care to those in need for 40 years. She retired in 1973 and died on her beloved island on August 26, 1975. After her death in 1975, islanders had these words engraved on her tombstone: "Well done thy good and faithful servant. Enter into the joys of the Lord."

Above image: Kathleen Bragg in her school office, circa 1950s.